PRSA So-Called “Clean Audit” Conflicts Reported to U.S. PCAOB

Public comments to the PCAOB discuss PRSA's audit and conflict of interest issues overseen by PRSA's CFO (Global Alliance's Treasurer).

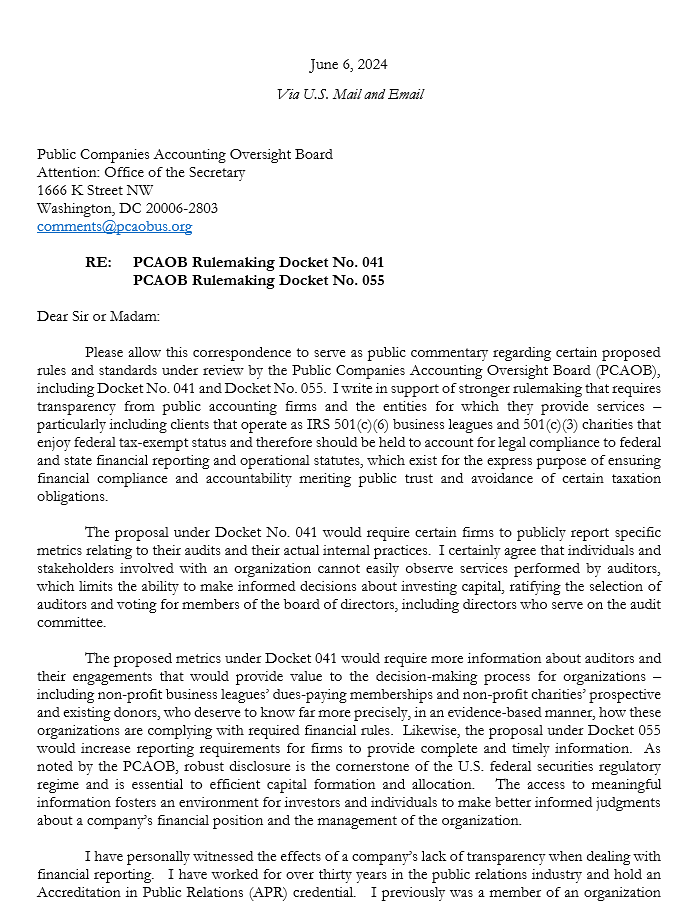

This week, I responded to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s (PCAOB) invitation for public commentary about two new rule-making initiatives under consideration, potentially to improve audit standards implemented by corporate audit functions and independent auditing firms.

For those who operate outside the U.S. and are unfamiliar with this agency, according to its website, the PCAOB was “established by Congress to oversee the audits of public companies in order to protect investors and further the public interest in the preparation of informative, accurate, and independent audit reports. The PCAOB also oversees the audits of brokers and dealers registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), including compliance reports filed pursuant to federal securities laws.”

The PCAOB operates by a “speak-up” culture and relies on public tips about observed misconduct:

My comments to the PCAOB this week support much-needed rule-making that might prevent the types of misconduct I have witnessed as a former member and ongoing observer of PRSA, which enjoys tax-exempt status and is subject to New York Not for Profit Corporation Law and financial reporting statutes.

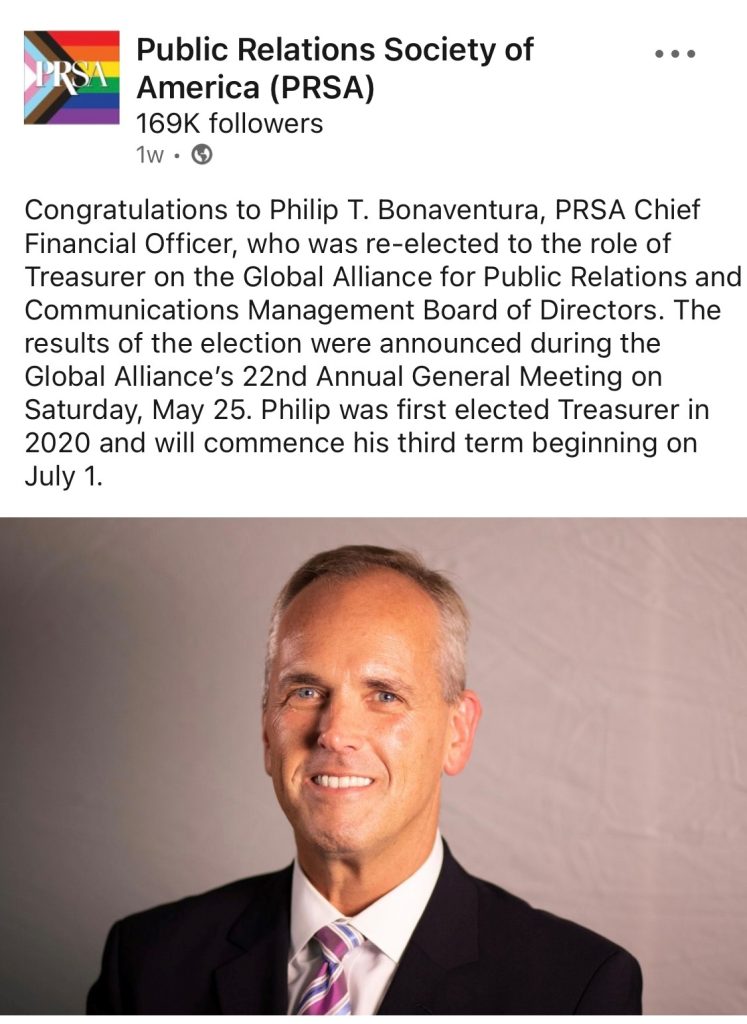

For more than 15 years, the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) and the PRSA Foundation (which share the same CFO) have used the same auditor, PKF O’Connor Davies, for both tax prep and auditing services for both organizations, as overseen throughout this entire timeline by PRSA’s CFO, Philip Bonaventura.

A 15-plus-year continuous engagement by one single tax prep + audit firm runs afoul of basic best-practice in fiduciary oversight for any organization — including a tax-exempt business league such as PRSA, Inc., and related but separate charitable entity such as the PRSA Foundation. The outside auditor contract should turn over at least every three to five years or so, in order for fresh sets of eyes to place much-needed scrutiny on the financial figures and practices of the entity under audit.

But this hasn’t occurred in PRSA, which is deeply concerning in and of itself.

However, other ethics / compliance issues have abounded — all of which have been reported multiple times in the public domain, which PRSA has ignored — calling into serious question whether PRSA’s auditor claims of a “clean audit” for PRSA and the PRSA Foundation pass any basic standard of authenticity, given all that’s going on in the background.

Documented issues include:

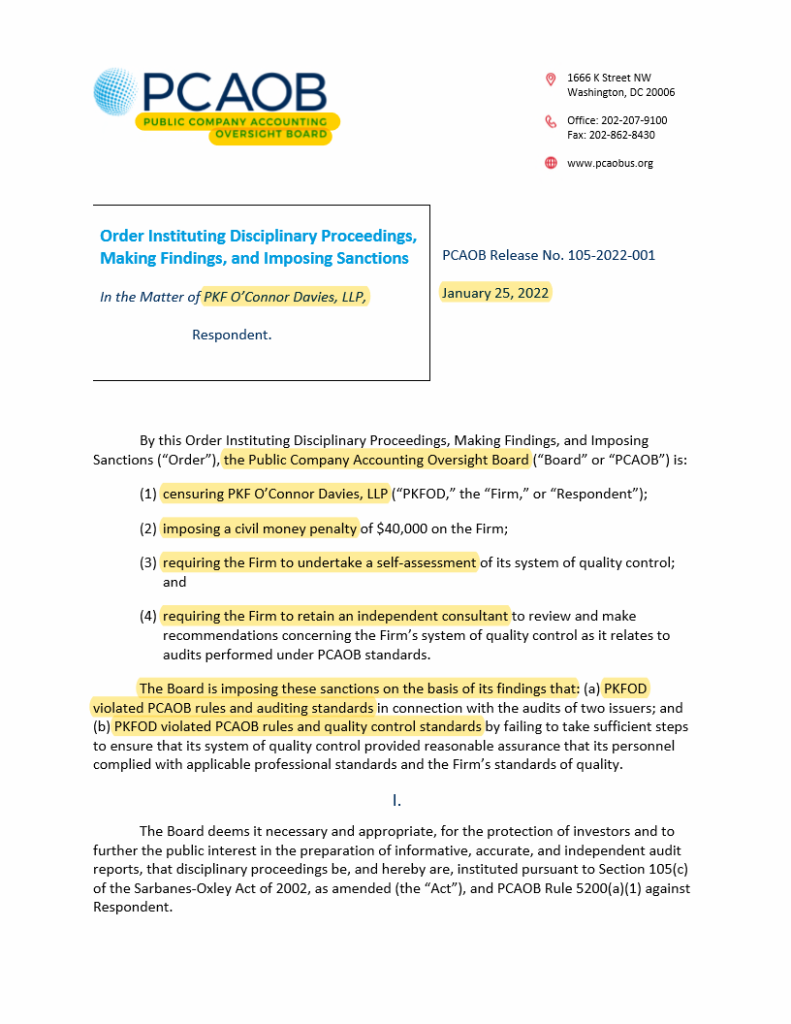

- PRSA’s own auditor, PKF, has been sanctioned by government agencies for serious audit service failures and rule-violations, yet PRSA — by CFO Bonaventura’s own recommendation — has continued to retain the firm.

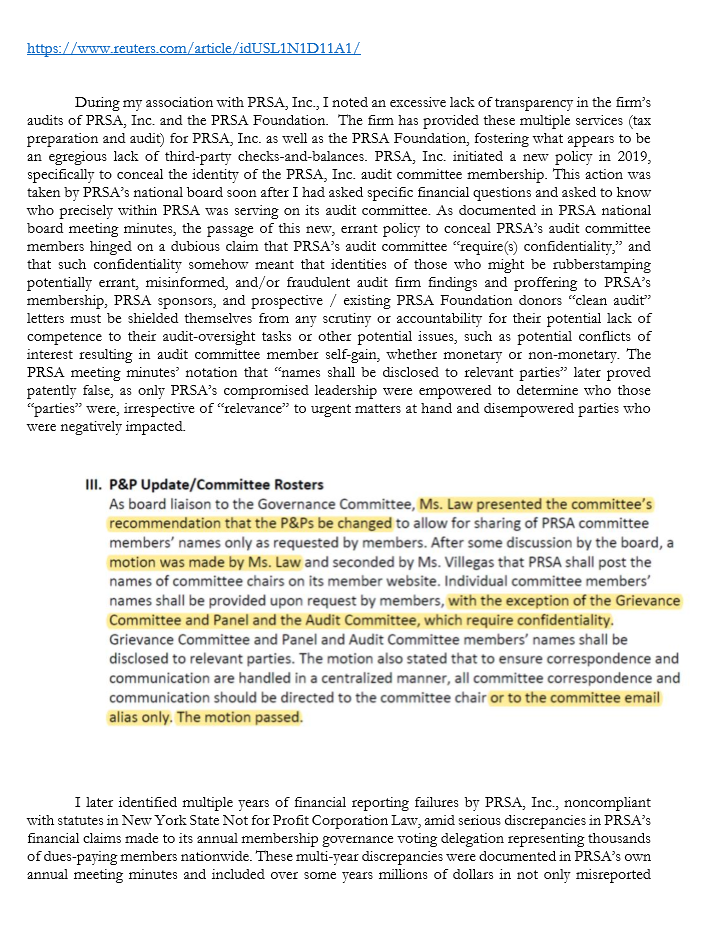

- PRSA began concealing the identities of its own audit committee in 2019, the same year I began asking serious questions about PRSA’s finances, when it became apparent PRSA had retroactively changed a prior “audited” financial statement, without member notice and without logical explanation for the specific line-item change.

- PRSA has engaged in other unannounced and unexplained retroactive changes in its so-called “audited” financials, alongside major discrepancies of financial performance reported to PRSA’s voting Assembly delegation versus reported to the Internal Revenue Service via PRSA’s Form 990 filings. These issues have been reported but remain unaddressed and unresolved by the Office of the New York Attorney General.

- PRSA posted in December 2023 a legally noncompliant, 11-month financial statement (balance sheet), rife with math errors totaling more than $5 million. The errant balance sheet remained posted online for some two weeks and only was changed after I reported publicly the discrepancies. PRSA CEO Linda Thomas Brooks subsequently told a PRSA member who directly contacted her about these discrepancies that the math errors as clearly documented were not math errors, but instead, as she claimed, “graphic design” errors. This false claim incurred a major PRSA ethics violation, by way of PRSA’s CEO issuing disinformation, with intent to mislead a dues-paying stakeholder while also casting fault / blame on an innocent graphic designer, who simply took receipt of the math-error-riddled financial data they were handed by CEO Thomas Brooks and CFO Bonaventura.

- PRSA CFO Bonaventura continues to ignore PRSA’s Code of Ethics, via its “Conflict of Interest” tenet, which clearly states that those associated with PRSA must “Avoid real, potential or perceived conflicts of interest” in order to “build the trust of clients, employers, and the publics.” Yet despite this mandate, Bonaventura serves concurrently in multiple roles controlling financial transactions and purse strings as CFO of PRSA while also serving multiple years as Treasurer of the Global Alliance (GA), with which PRSA does business as a dues-paying organizational member of the GA.

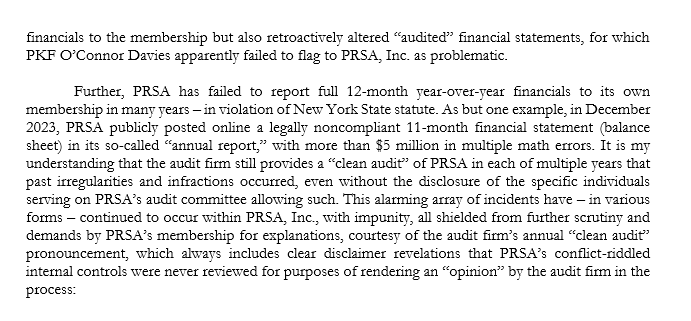

PRSA purposely contracts with its auditor, PKF, a narrowly defined audit scope that disallows PKF to offer an “opinion” on PRSA’s or the PRSA Foundation’s internal control.

This “no opinion” stance on PRSA’s internal control essentially greenlights a garbage-in / garbage-out methodology for PRSA’s and the PRSA Foundation’s audit function, with PKF obligated to accept at face value the financial information that CFO Bonaventura and CEO Thomas Brooks hand over to the audit firm as purportedly “valid,” with or without “graphic design” non-math errors, or whatever else they’ve cooked up.

Put another way, there’s little or limited kicking-the-tires or checking under the hood of PRSA’s financial data, as to precisely how their data has been derived in the first place — including whether serious conflicts of interest are baked in to PRSA processes, procedures, and non-compliance problems yielding the data itself.

For those unfamiliar with accounting and audit terminology, according to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), “internal control” is defined and specified as follows:

Internal control over financial reporting is a process designed by, or under the supervision of, the company’s principal executive and principal financial officers, or persons performing similar functions, and effected by the company’s board of directors, management, and other personnel, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the reliability of financial reporting and the preparation of financial statements for external purposes in accordance with GAAP and includes those policies and procedures that –

(1) Pertain to the maintenance of records that, in reasonable detail, accurately and fairly reflect the transactions and dispositions of the assets of the company;

(2) Provide reasonable assurance that transactions are recorded as necessary to permit preparation of financial statements in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, and that receipts and expenditures of the company are being made only in accordance with authorizations of management and directors of the company; and

(3) Provide reasonable assurance regarding prevention or timely detection of unauthorized acquisition, use, or disposition of the company’s assets that could have a material effect on the financial statements. 1/

Note: The auditor’s procedures as part of either the audit of internal control over financial reporting or the audit of the financial statements are not part of a company’s internal control over financial reporting.Note: Internal control over financial reporting has inherent limitations. Internal control over financial reporting is a process that involves human diligence and compliance and is subject to lapses in judgment and breakdowns resulting from human failures. Internal control over financial reporting also can be circumvented by collusion or improper management override. Because of such limitations, there is a risk that material misstatements will not be prevented or detected on a timely basis by internal control over financial reporting. However, these inherent limitations are known features of the financial reporting process. Therefore, it is possible to design into the process safeguards to reduce, though not eliminate, this risk.

SOURCE: https://pcaobus.org/oversight/standards/archived-standards/pre-reorganized-auditing-standards-interpretations/details/Auditing_Standard_5_Appendix_A#:~:text=Internal%20control%20over%20financial%20reporting%20is%20a%20process%20designed%20by,personnel%2C%20to%20provide%20reasonable%20assurance

My public comments as registered to the PCAOB this week are as follows:

Due to all issues enumerated above, I strongly urge organizational members of the Global Alliance to rethink their apparent rubberstamping of PRSA CFO Bonaventura as their organizational Treasurer for the Global Alliance.

This matter is of particular concern, given that even if money laundering and similar financial crimes are not occurring in the Global Alliance or in PRSA as I certainly hope that they are not, this set-up of Bonaventura essentially being allowed to control and directly influence / oversee purse strings of two separate organizations that are doing business with each other — including, at a minimum, the financial transaction of Bonaventura cutting PRSA’s organizational dues check (how much, we have no idea) to the Global Alliance, which Bonaventura then accounts for receipt in his role as Global Alliance Treasurer — creates an automatic scenario of appearances of conflict-of-interest.

As stated, this set-up not only violates the letter and spirit of PRSA’s own ethics code, but it arguably violates the so-called ethics code of the Global Alliance itself, which, like PRSA’s so-called ethics code, is unenforced but claims to espouse an “avoiding conflict of interest” provision.

Apart from those not-so-minor points, it’s just plain stupid, from any reasonable vantage point of fiduciary care.

Any checks-and-balances ethic here is being utterly ignored and flouted by the conflict of allowing PRSA’s CFO to serve as the GA’s Treasurer.

PRSA’s own auditors — which have a recent documented history of not exactly doing their audit jobs well — apparently also ignore (or simply haven’t been notified by Bonaventura) that he controls finances of two organizations doing business with one another.

Anyone who argues that this set-up does not present appearances of a conflict of interest is likely the same person arguing that ethics codes are mere “guidelines” and that we simply need to “trust” the folks in leadership on a Scout’s-Honor wing and a prayer.

What do you think of these issues? Do Bonaventura’s dual roles harm ethical compliance in the PR industry?